The Amazing Radio London Adventure |

In at the Deep End – dodging management cross-fire and breaking-in deejays

The next day I left Lisbon and arrived in London in about two hours. It was November 11th, 1964.

I met Don Pierson at the Hilton Hotel and he checked me in. After talking to him for a while, I realised there was quite a bit of friction between Don and Philip Birch, who was running Radio London's sales organisation, Radlon Sales.

Philip was a Canadian whose parents had been British subjects. He later became a naturalised American, so he was entitled to carry three different passports. He was an obsessive Anglomaniac who at times was more English than the British.

Philip was a Canadian whose parents had been British subjects. He later became a naturalised American, so he was entitled to carry three different passports. He was an obsessive Anglomaniac who at times was more English than the British.

Philip gave the appearance of being very thoughtful about all things. However, I am convinced that this was a façade that he presented to throw his competitors off guard - and everyone was his competitor.

Don Pierson, on the other hand, was direct and to-the-point and sometimes hurtful to the people he dealt with. Not only that, but Don was very secretive about the things he was involved with. It seemed that he took great pleasure in withholding information from his business partners, then at the last minute would divulge something that they should have been made aware of long before.

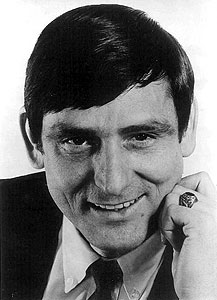

(left, Ben in 1965)

Philip and Don were savage competitors. Not only should they have been in separate rooms, but also separate continents. At this juncture I must point out that had it not been for the persistence of Don Pierson, there would not have been a Radio London of great importance. Time was of the essence and if Don had not pushed things along as he did, we would have never been able to regain our costs and to show a profit of any size.

Don had failed to keep Philip abreast of what was going on, and Philip and his two salesmen, Alan Keen and Dennis Maitland, were wandering around London trying to sell something they knew nothing about. At first they didn't even know the station name and were selling it as 'Radio X'. Philip had thought of calling the station 'Radio Galaxy'. However, unknown to Philip, Don had already named it Radio London, and had contracted to have jingles recorded in that name. There was a definite breakdown in communications between Don and Philip, and there was not a great amount of interest on the part of either party to come to reconciliation.

Mal McIlwain was one of the senior partners in Radio London. He had been the Ford automobile dealer in Abilene, Texas and he and Philip Birch had become friends when Philip was a time-buyer for J. Walter Thompson in New York. The Thompson agency handled the Ford Motor Company account throughout the country. Philip would go to McIlwain with all his problems, bypassing Don. Don was outraged at this kind of behaviour from one whom he considered to be a subordinate. So, this was the state of affairs when I arrived in London.

The day after I arrived in London, Don flew down to Lisbon. This left me in the hands of Philip Birch and his salesmen at 17 Curzon Street. Philip et al naturally wanted to know what the hell was going on. They wanted to know what my ideas were on programming and they especially wanted to know how they were expected to sell it.

I told them that we would have Top Forty radio. I emphasised that this type of radio plays all the top songs of the day with a few oldies thrown in. I explained that this format had been used in every major market in America and that in practically every market, the Top Forty station was number one. I explained that I did not intend to have any canned or block programming whatsoever, and that I expected to have deejays on the ship at all times to deliver the programmes.

I don't think this immediately soaked in. All three had become accustomed to the block programming of the BBC where they would have the farm show followed by the garden show squeezed between Pete Murray or David Jacobs. The sales team had in their minds that a variety of music from Mantovani to Frank Sinatra to Elvis Presley would be delightful.

Alan Keen told me how much he liked jazz and that he was a big fan of Mel Tormé. I reminded Alan that jazz had a very limited audience. Even though Mel Tormé was regarded as a singer's singer, he sold very few records and most of those sales were around Christmas time when his fans purchased copies of the Christmas Song. I told Alan that we had to programme the station to gain the highest listenership and that I was sorry, but Mel would just have to go.

While Don Pierson was in Portugal, Philip Birch put me in touch with Maurice Sellars and Roy Tuvey who agreed to help me locate some deejays. Within a few days, I started getting some replies; however, very few of the persons who applied had the kind of experience I was looking for. I can't recall the exact sequence in which I hired the deejays, but among the first were Tony Windsor, Pete Brady, Kenny Everett, Duncan Johnson, Paul Kay and Earl Richmond, shortly followed by Dave Cash and Dave Dennis. The following year I brought on board John Edward, Mark Roman, Ed Stewart and Mike Lennox.

Right: Deejay jam session (minus the jam) in the mess aboard the Galaxy. l to r, Pete Brady, Paul Kay, Earl Richmond, Duncan Johnson, Tony Windsor and Kenny Everett, with Dave Cash kneeling

The only deejays who had commercial radio experience were Dave Cash, Tony Windsor, Pete Brady and Duncan Johnson. However, Dave and Tony both had the basic qualities I was looking for and I was hoping that the two of them would be able to fine-tune the others and help them to create a live and vital sound, which is the trade mark of Top Forty radio.

I was in the midst of hiring deejays when Don Pierson returned from Lisbon. Don loved to entertain himself by searching out important people and somehow he had run into the Everly Brothers. Knowing that he was putting together a radio station, they invited him to a private party. They also suggested that he bring along his programme director. When Don asked me if I would like to go to the party, and I immediately accepted. My previous week had been taxing and a party was just what I needed to take the edge off the most unrealistic state of affairs I had ever been thrown into.

The following evening, Don and I made our way to the party. The host had a rather large upstairs flat with a balcony that looked out over the street. Don and I said hello to Don and Phil Everly and I reminded them that we had met several years before at the West Texas State Fair in Abilene. They said that they remembered me, but artists always say that. It is a sort of knee-jerk reaction in those circumstances. Nonetheless, the two Dons struck up a conversation out on the balcony and Phil and I retired to the living room to chat up a couples of 'birds'.

The music was loud and the noise level from the large number of people in the room was rather high. Phil and I were engrossed in our conversations and were not paying much attention to what was going on around us. Suddenly Don Pierson appeared from outside and drew my attention to an attractive young woman standing high on the grand piano, divesting herself of her clothing. She was keeping perfect time with the music, and it occurred to me that she had had some formal training. She eventually undressed until all she had left on was a smile.

Don Pierson was aghast, to say the least. He was from a small town in Texas where the most excitement they had was talking about 'Old Rip'. 'Old Rip' was a horned toad that was reputedly found alive inside a rock which was broken open while building the local courthouse.

Don said, "Ben, I don't think I have ever seen anything like this in my life. Did you see that girl? She just stood there and stripped everything off!" I said, "Well, Don, welcome to the Sixties."

The closer we came to getting on the air, the more people came flooding into 17 Curzon Street. The salesmen had clients arriving, while I had record producers, artist agents, music publishers, and exploitation representatives from the record companies stopping by. It became chaotic.

In the midst of all this, Don Pierson and Philip Birch were firing-off verbal blasts at one another, which left me walking a tightrope between them.

Finally on November 19th 1964, the Galaxy arrived in the Thames Estuary. Nothing had changed since I had left Madeira and the captain and the crew were still in a state of frustration.

Art Nobo had not been able to work on the transmitter at sea, and apparently Bill Carr had done very little to solve the transmitter problem in Lisbon.

I do not want to imply that Art and Bill were incompetent. To my knowledge this was the first time anyone had tried to install a 50,000 Watt radio station on a ship, and this whole project was experimental. In the end, it took over a month for RCA Belgium to get the transmitter power up to 17,000 Watts, and it took several more months to get the station up to full power. This was a tremendous undertaking.

By the time the ship had anchored 3.5 miles off Frinton-on-Sea, Essex, Art Nobo was ready to go home. He was seasick, homesick, and generally sick of the ship, so as soon as he could find a boat to take him ashore and get a plane ticket in his hand, Art was gone.

By 1970 I had returned to the States and was a representative for a regional radio network located in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. I was in Jackson, Mississippi on business and staying at the Sheraton Inn. One afternoon, I returned to the hotel from a visit to one of the local radio stations. Just as I walked through the door there stood Art Nobo, talking to two other men. Art told me that shortly after he returned to Miami, he got a job as an engineer with RCA. He said that they had transferred him to Atlanta, Georgia, and that he was in Jackson for an RCA convention which was being held at the Sheraton Inn. He was back with his wife and they were both very happy.

Things did not work out so well for Bob Ables. I never knew if he was sacked or if he left the ship of his own volition, only that shortly after the Galaxy arrived, Bob left the ship and flew home. A short time later, Philip Birch called me into his office and delivered the sad news that Bob had been killed in a car crash in Texas.

Fortunately, when Bob Ables left, we had Dennis Maitland to step in and perform the almost impossible tasks that Bob had been expected to do. Very early on we had discovered that the Galaxy's ancient generators were unsteady and unable to cope with operating the radio station and the ship's power supply simultaneously. Don Pierson had arranged with Cummins Diesel to have a 60 cycle (Hertz) generator transported from the U.S. The 50 cycle generator which was used in the UK was incompatible with our broadcast equipment. Nonetheless, Don made arrangements for the generator to be sent over, and it was up to Dennis to get the generator out to the ship and have it installed on the wing of the bridge.

Among Dennis's other duties were finding parts needed for the transmitter and getting proper anchors installed to keep the ship well in place during bad weather. All these jobs were on Dennis's plate in addition to working as an airtime salesman in the London office. He proved to be an invaluable asset to getting the station off and running.

Within a few days after the Galaxy was anchored, Captain Walters was relieved of his duties to be replaced by a Dutch captain who was in turn, soon replaced by another Dutchman, Captain Bill Buninga. Captain Buninga had worked for many years at sea with the Shell Oil Company and was respected by all who knew him. He captained the Galaxy through most of her stay off Frinton-on-Sea.

There were originally about sixteen West Indians on board during the time we crossed the Atlantic. By the time Captain Buninga joined the ship, about half of them had been sent back to the States, and of course the captain replaced them with Dutch seamen.

The Dutch and the West Indians mixed about as well as oil and water, so the Dutch seamen began a campaign to get rid of the original crew. It was reported to me by the West Indian ship's engineer that the Dutch had thrown bolts down the stack in an attempt to kill the West Indians. I asked Captain Buninga about this and he told me that he knew nothing about it, but he would try to get to the bottom of it. I was sure that the captain had had nothing to do with any of this, but several of his seamen were more than a little wild, which convinced me that the engineer had been truthful in his report.

As it happened, all the West Indians were gone in short order, and the only ones left who had crossed the Atlantic were me and Michel 'Mitch' Philistin, the 19-year-old Haitian cook. My young friend Mitch had a very long stay on the ship. He had not brought his passport, so he was afraid if he went through immigration, the authorities would send him back to Haiti rather than to the US. Had that happened, Mitch was likely to have been conscripted into the Haitian Army, which he considered a fate worse than death. So he stayed aboard the Galaxy for over a year. Finally, Philip Birch, through some of his connexions, obtained a permit for Mitch to go on land for limited stays. Mitch fell in love and married a British subject, which then allowed him to obtain a permanent visa. All the deejays and I thought a lot of our friend Mitch and we still do.

When the ship arrived at its anchorage, I sent my newly-recruited deejays on board to check out the studio equipment and listen to my recordings of KLIF to get a feel for Top Forty format. I stayed on board for a time to familiarise them with the setup. As I remember it, I had no choice, as the winter seas were so bad that I couldn't get off for about a week.

The station made it on the air at 0600 on December 23, 1964. Paul Kay made a brief announcement, "Good morning ladies and gentleman, this is Radio London transmitting in the medium wave band on 266 metres, 1133 kilocycles." And with that, Pete Brady kicked off his morning breakfast show.

The station made it on the air at 0600 on December 23, 1964. Paul Kay made a brief announcement, "Good morning ladies and gentleman, this is Radio London transmitting in the medium wave band on 266 metres, 1133 kilocycles." And with that, Pete Brady kicked off his morning breakfast show.

Although most of my newly-hired deejays had no commercial broadcasting experience, they caught on to the operation of the equipment quite easily. It was their delivery that needed improvement to suit Top Forty radio. Tony Windsor was not too bad. He sounded very professional, with a good amount of vitality and with a little added reverb, he sounded even more alive. Pete Brady, Paul Kay, and Earl Richmond were the ones who needed a fire built under them. I especially wanted Pete to be more upbeat, because he was to do the morning breakfast show. Within a few weeks of going on the air, Pete showed a marked improvement.

(Left: Grub's up! Ed Stewart and Ben in the mess, 1965)

Although Earl Richmond made some improvement over time, he never really came up to my expectations. He always portrayed an air of affectedness, that made me visualise him sitting at the mike with a plum in his mouth and wearing the old school tie.

I don't think Paul Kay had it within himself to be what I wanted him to be. He was already in his thirties and had been well-schooled in the formal BBC style. He wanted to be a deejay, but I needed a newsman, so I asked him if he would like to do news. He thought for half a second and said yes. So Paul Kay became our newsman, and a damn good newsman he was.

Young Kenny Everett, our 19-year-old trainee, listened to all the KLIF tapes, and before long he was doing all the things I had hoped the other deejays would be doing. It didn't take him long to understand what Top Forty radio was all about. Later, when Kenny teamed up with Dave Cash, they were a knockout combination.

About three months after we want on the air, Pete Brady began to have problems living at sea. He left in October 1965 and had to be replaced. The deejays brought one of their young friends to me whom they had worked with on their live appearances on land at the Wimbledon Palais. Graham Wallace had been a disco deejay, but had no experience on the air. He sounded pretty good on tape, so I brought him on board as a relief deejay under the name Mark Roman.

Sometime later, Kenny Everett displayed a total lack of professionalism by making degrading remarks about one of our sponsors, Garner Ted Armstrong and his program, The World Tomorrow. This was a 30-minute religious program that had been contracted prior to my arrival in London. It was a £50,000 yearly contract which helped to defray many of the station's expenses. The content was totally out of my Top Forty format, but the program ran at 7pm, outside of prime time hours.

Kenny hated The World Tomorrow because it cut right into the Kenny and Cash Show which started at 6pm. I know that Dave must have hated this situation as well, but Dave was one of the most professional broadcasters I have ever known, so I'm sure he understood how much this program meant to our existence.

Nevertheless, Kenny kept making his caustic remarks. I warned him twice, but upon his third offence, Kenny was gone. It was my opinion that he had become tired of being on the ship, but he was embarrassed to come to me and resign, since I had given him such a great break in his career. So in the end he forced me to sack him.

Nevertheless, Kenny kept making his caustic remarks. I warned him twice, but upon his third offence, Kenny was gone. It was my opinion that he had become tired of being on the ship, but he was embarrassed to come to me and resign, since I had given him such a great break in his career. So in the end he forced me to sack him.

Kenny and I were still good friends. A number of years later both he and Dave were working for Capital Radio in London. The three of us, with Capital's programme controller, Aiden Day, met for lunch at Trader Vic's in the Hilton Hotel. Kenny and I had a big laugh about me sacking him from Radio London (although he did return to the station in June 1966). Kenny was to become one of the all-time-great radio/TV personalities in the UK. Unfortunately, he left us all too soon with his untimely demise in 1995.

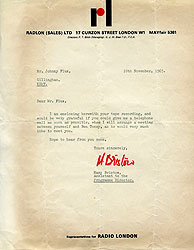

(Left: the Curzon Street response to John Edward's demo tape, dated Nov 10th 1965, inviting him to meet Ben. Click on letter to see an enlarged version. Image courtesy of John Edward's personal archive.)

After Kenny left the ship for the first time, I brought in John Edward. He had worked for Radio City, the fort-based station, as Johnny Flux. Before that, John had played guitar for several groups including the Manish Boys whose lead singer was Davie Jones, later known as David Bowie. John Edward and Paul Kay likely had some good times playing their guitars on board the ship. Paul was quite an accomplished guitarist in his own right.

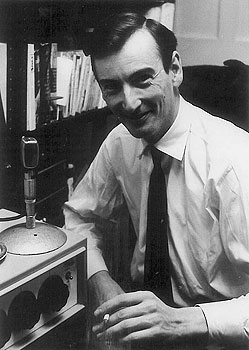

Before I end my discussion of the deejays, I must mention Dave Dennis (right, pictured in 1965) who in my opinion made the greatest amount of progress of them all. Dave was basically an actor and like the other English deejays, he had been brought up on listening to the BBC. Dave was quite a loner and kept very much to himself on the Galaxy. Tony Windsor was the chief deejay, and I had given Tony instructions to break Dave in and give him a few tips on how to present a proper deejay show. Tony at times was overly-enthusiastic when giving instructions and in the end I could tell he was about to drive Dave around the bend. I finally told Tony to leave Dave to me and I would train him myself.

Before I end my discussion of the deejays, I must mention Dave Dennis (right, pictured in 1965) who in my opinion made the greatest amount of progress of them all. Dave was basically an actor and like the other English deejays, he had been brought up on listening to the BBC. Dave was quite a loner and kept very much to himself on the Galaxy. Tony Windsor was the chief deejay, and I had given Tony instructions to break Dave in and give him a few tips on how to present a proper deejay show. Tony at times was overly-enthusiastic when giving instructions and in the end I could tell he was about to drive Dave around the bend. I finally told Tony to leave Dave to me and I would train him myself.

I was only on the ship about once a week, so Dave didn't see much of me. But, when I was aboard, I was very explicit about what I expected of him. I began by playing on Dave's artistic talent as an actor. I instructed him to listen to the KLIF tapes whenever he had spare time. I then told him that if he were any kind of actor, he would be able to create the style of programming recorded on the tapes. As it turned out, Dave went from being a stuffy announcer to a top-notch deejay in a matter of weeks.

Although the deejays played a significant role in the making of Radio London, this text has more to do with my own experiences with Radio London and other ventures. Two magnificent books that give full details of the deejays and their backgrounds are 'Pop Went the Pirates' written by ex-Radio Caroline and ex-Radio London DJ, Keith Skues and 'The Wonderful Radio London Story', written by my friend Chris Elliot.

Some months after Radio London went on the air, deejay Joey Reynolds from one of the major stations in New York, approached me about the possibility of running canned programs that he would record and ship over to me weekly. I said I was not interested. He then told me that I needed to build a fire under my deejays, so I asked him what his New York ratings were. He proudly announced that he had an audience of about 3,000,000. I said, "Well, Joey, you need to do a lot better. My deejays have an audience three times that size." I never heard from Joey again.