Most people outside Europe (especially DJs) are amazed to hear about the limited choice of radio available in the UK prior to 1964. Before then, few UK radio listeners had heard a commercial on the radio, let alone a jingle...

By

the time Top Forty radio arrived in the UK, the Golden Age of American

radio was practically over. We didn't have much to listen to before

the advent of the offshore 'pirates'. The BBC did have a few pop programmes

on what was called 'The Light Programme'. Besides the Light Programme,

the BBC (later christened 'the Beeb' by Kenny Everett), had 'The Home

Service' (news and speech-based), 'The Third Programme' (highbrow classical

music and avant-garde drama) and 'The World Service' [which oddly

enough was barely audible in Britain, but was in the rest of the world!

– Chris]. In the early Sixties, teenagers were a relatively new concept and catering for their musical tastes was not considered a top priority by Beeb management. Pop music was regarded as merely a passing fad. However, one of the Beeb's greatest difficulties with regard

to playing records was 'needle-time', a regulation whereby

only a certain number of minutes of recorded music was permitted to

be played weekly. This was due to Musicians' Union agreements and the

fact that the BBC employed its own orchestras; playing recordings off

vinyl would have cut down on the need for BBC-employed musicians.

One of the week's highlights for many people - and not merely the teens – was 'Pick of the Pops',

a chart countdown show broadcast on the Light Programme, initially on Saturday

nights and then moved to Sunday afternoons. Before the pirates arrived,

you could go to a beach, a park or any other public place on a Sunday

and hear 'Pick of the Pops' without owning a radio! All the car radios

and portables would be tuned in and the show could be heard everywhere

you went. The presenter associated more than anyone else with 'Pick

of the Pops', was the late Alan 'Fluff' Freeman. Fluff made the programme

his own, coining catchphrases such as "Hi there, pop-pickers!"

The only worthwhile listening option that we discovered other than the BBC was Radio Luxembourg,

a commercial broadcaster with a very long history. The station output was transmitted

from the tiny country of Luxembourg every night on 208 metres Medium

Wave, but most of the shows were pre-recorded in London. I remember

my shock when I first encountered 'Luxy' at around the age of ten. (i.e.

circa 1960) I had never before heard a commercial on the radio! Once

I discovered a station that played pop music nightly, I tuned in every

single evening, like thousands of other pop-starved kids. At the earliest

opportunity, I acquired  a cheap reel-to-reel tape machine to capture

the current hits and especially the American music being played on

Luxembourg.

a cheap reel-to-reel tape machine to capture

the current hits and especially the American music being played on

Luxembourg.

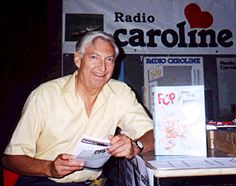

(Left: Tony Prince was on both Luxembourg and Caroline)

Reception was frequently very poor and the station inevitably faded into oblivion just as the DJ started spinning your current fave, faded back, went distorted and (if you were lucky) settled down for about thirty seconds, before the whole process started again! (Lucky Luxy will forever retain a place in radio history, because 'The Luxembourg Effect' became a recognised technical term for this form of reception artefact.) Maybe kids in the US encountered similar problems with XERB and the other stations that blasted over the border from Mexico?

Luxembourg programmes were sponsored by the major record companies, so a 'chart countdown' on 208 was likely to consist solely of the bestsellers on Decca, or on EMI. These shows normally featured only the first part of a song before it was faded by the DJ. The thinking behind this was 'leave 'em wanting more - if they like the bit they've heard they'll go and buy the single'. Some of the programmes were only 15 minutes long and all of the company's new releases had to be crammed into that time-slot. With the combination of fading out by the DJs and fading out with the 'Luxembourg Effect' you were lucky to hear 30 seconds of a song. Most singles were three minutes or less in duration in the first place!

Radio apart, kids would hang about for hours in record stores, standing

in booths to listen to the latest releases, till they got thrown out

for failing to buy anything. Or else they would spend every spare coin

feeding the local jukebox. My friends and I used to love it when the

travelling fair came to town. Apart from the exciting rides, we'd go

just to listen to the music. They always played terrific records, which

would slow down and gather speed again as the electrical generators

coped with power dips and surges when the rides started and stopped.

Most people living outside of Europe (especially DJs) are amazed to

hear about the limited choice of radio available in the UK prior to

1964 and the extraordinary hardships the pioneers had to endure in order

to bring the public the music it wanted! Unfortunately, in Ben Fong-Torres's

US-published book, 'The Hits Just Keep On Coming', the chapter on UK

pirate radio is very poorly researched and inaccurate and will have

failed to have enlightened any of its readers!

Imagine how astonished the remaining members of the wartime crew of

the USS Density were to discover that their minesweeper had not

been scrapped, (as they had been informed by the US Navy) but had lived

on to become a radio station! The sad thing is that they never knew

at the time that their ship was home to a station called Radio London

and was anchored three miles off the coast of Essex with the new ID

of 'Galaxy'.

There are many younger people in the UK who have never heard of Radio

London and are unaware of the history of how Britain came to have commercial

radio and jingles. This is unlikely to be taught in schools

as a significant aspect of social change in the Swinging Sixties, even

though it certainly was.

The following is a brief history of Radio London:

Radio

London broadcast from 16th December, 1964 (the first test transmissions)

to August 14th, 1967, from the mv Galaxy, anchored outside the

three-mile limit of British territorial waters. This was in order to

circumvent the country's stringent broadcasting laws; at the time, BBC

radio was the only station licensed to broadcast in the UK. The stations

were dubbed 'pirates' by the press, but because the stations were broadcasting

from International Waters, which are ungoverned by any laws, their operations

were never actually illegal. What they were 'pirating' was mediumwave

frequencies.

Radio

London broadcast from 16th December, 1964 (the first test transmissions)

to August 14th, 1967, from the mv Galaxy, anchored outside the

three-mile limit of British territorial waters. This was in order to

circumvent the country's stringent broadcasting laws; at the time, BBC

radio was the only station licensed to broadcast in the UK. The stations

were dubbed 'pirates' by the press, but because the stations were broadcasting

from International Waters, which are ungoverned by any laws, their operations

were never actually illegal. What they were 'pirating' was mediumwave

frequencies.

Radio London's backers were Texan businessmen, headed by the late Don

Pierson, who had been impressed when he read a newspaper article concerning

the success of Radio Caroline, Britain's first offshore pirate radio

station. It was June 1964, and Don, the town mayor of Eastland, Texas,

was well aware of the huge success of local radio station KLIF. He felt

it was time to introduce American Top 40-style radio to the UK, his

aim being to model the station output on that of KLIF, calling it 'KLIF

London'. Don's original idea was for the new station to broadcast tapes

of the KLIF output, with the local jingles replaced by specially-made

'KLIF London' jingles. However, Don had to modify his ideas somewhat.

The British public was totally unfamiliar with upbeat American radio,

and had so far never even heard a jingle. It was feared that this style

of broadcasting would not attract conservative British advertisers.

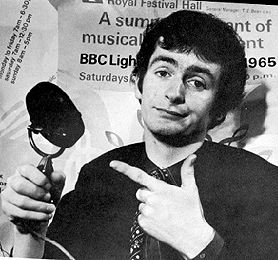

(Right: One of Radio London's original DJs, master of innovation, Kenny

Everett)

Another

Texan, Ben Toney, was brought in as Programme Director. Ben had worked

in the radio business for eight years, and was currently both sales

manager and DJ at WTAW in Bryan College Station. Radio London's jingles

were also recorded in Dallas, by PAMS, (Promotions, Advertising and

Merchandising Services) the top US jingle company at the time. Ben spent

some weeks in Dallas, overseeing production of a new set of PAMS Radio

London jingles, and consulting with KLIF's owner, Gordon McLendon and

his staff, to produce a station format for the new pirate station, similar

to KLIF's. To stay ahead of the four existing offshore pirates which

were currently broadcasting from forts and ships, Radio London would

become the first to carry news bulletins.

The backers searched for an appropriate ship to sail in Caroline's wake,

eventually purchasing the mv Density, a former US minesweeper.

They converted the ship for broadcasting use in Miami, renamed her the

Galaxy, and sailed her across the Atlantic Ocean to a new home;

an anchorage approximately three miles off Frinton-on-Sea, Essex. The

station's on-air name was agreed upon as Radio London – Big L,

just as KLIF Dallas was known as Big D. Ben Toney recruited DJs who

had gained on-air experience in Australia, Canada, Kenya and the USA.

When the station opened officially on December 23rd 1964, Canadian Pete Brady kicked off the very first broadcast with the following words: "Radio London is now on the air with its regular broadcasting schedule. This station will bring to Britain the very latest from Radio London’s top 40, along with up-to-date coverage of the news and weather. Radio London promises you the very best in modern radio".

Big

L's novice DJ was 19-year-old Liverpudlian, Kenny Everett. Ben Toney

immediately spotted star quality in Kenny's idiosyncratic raw talent,

and the nervous youngster evolved into one of the UK's greatest-ever,

and much-loved DJs.

Ben gave Kenny Everett and the more-experienced broadcaster, Dave Cash,

tapes of KLIF to listen to and emulate. When they heard the Charlie

and Harrigan show (at the time, 'Charlie' was Danny McCurdy – a

jock who had once worked for Ben – and 'Harrigan' was Ron Chapman),

Everett and Cash decided they would like to attempt a similar, zany

programme. In April 1965, the Kenny and Cash show was born. Within weeks,

this anarchic and hilarious programme achieved cult status, and changed

the face of UK radio for ever – copied, but never bettered. The

show was only on the air for a matter of months, but it has never been

forgotten. Rare recordings of it are treasured by air-check collectors.

Dave Cash says he is amazed at how people still talk to him about a

show that ran for such a short time, back in 1965!

The

catchy PAMS jingles also achieved immediate popularity, and the station

went on to become the most successful of the British pirates. It was

Big L, and the influence of KLIF, that irrevocably changed British broadcasting.

The

catchy PAMS jingles also achieved immediate popularity, and the station

went on to become the most successful of the British pirates. It was

Big L, and the influence of KLIF, that irrevocably changed British broadcasting.

(Left: Keith Skues, pictured in August 2000, was on Caroline, London and Radio One. Oh, and also Luxembourg. Photograph - Pauline Miller)

When

a comparison is made, it quickly becomes apparent that the Big L Fab

Forties bear little resemblance to the sales-based charts of the time.

Radio London always tried to stay ahead of the game and by the time

a record had hit the top of the National Charts, it had usually been

dumped from the FF. It's the lesser-known singles from that era that

interest people the most. That is why the policy of our friends at the

Oldies Project

has always been to include as much material as possible that listeners

are unlikely to hear on their local 'Gold' station, with its boring,

repetitive playlist. (We know from first-hand experience that current

US radio is equally bad in that respect.) There were thousands of great

records released between the Fifties and the Seventies, so why is it

necessary for the audience to be bored rigid by a tedious little playlist?

Sadly there is now precious little radio that appeals to listeners who

enjoyed Big L back in the Sixties, which is why Oldies Project is proving

immensely popular.

In August 1967, the Wilson government's 'Marine etc., Offences Bill'

forced the closure of all but one of the pirate stations, Radio Caroline.

Its northern station broadcast from the mv Fredericia off the

Manx coastline and its southern ship was outside territorial waters

off the coast of Essex. Broadcasting from International waters could

not be made illegal, but working on the stations, supplying the ships

and advertising on the stations, could. There was a huge public campaign

to try and save offshore radio and the independently-governed Isle of

Man fought Westminster in an attempt to retain Caroline North. Most

of the stations ceased transmission on or before August 14th, 1967,

when the Marine Offences Bill became law at midnight.

Radio

London closed at 3.00pm on August 14th. The day continues to be well-remembered

and commemorated amongst radio fans, few of whom are able to listen

to recordings of the station close-down without their emotions getting

the better of them.

(Right:

Ed 'Stewpot' Stewart began his career on Big L)

Caroline was the only offshore pirate that managed

to keep both her stations (south and north) broadcasting after the Marine

Offences Act was passed. Both Carolines hung on for a few months more,

by the skin of their teeth, serviced and supplied from Holland. Life

on board became increasingly difficult, and in March 1968, the two ships

were forcibly towed away to Amsterdam in retaliation for unpaid bills.

BBC

Radio One was launched in September '67 as the first national pop station,

and was intended to be a replacement for the much-lamented pirates.

A large percentage of the DJs on the newly-launched station were recruited

from Radio London, although it was always going to prove impossible

to recreate the atmosphere of being strapped down in a bucking studio

on the North Sea! DJs used to operating their own turntables found the

job was being performed by technical assistants. Radio One, still dogged

by 'needle-time' restrictions, was also required to share airtime with

the more formal Radio Two. The substitute for record-spinning was live

music. Embarrassing 'live house band' versions of Hendrix hits tended

to somewhat mar the station sound and its intended 'with-it' image.

The Beeb had a lot to learn.

BBC

Radio One was launched in September '67 as the first national pop station,

and was intended to be a replacement for the much-lamented pirates.

A large percentage of the DJs on the newly-launched station were recruited

from Radio London, although it was always going to prove impossible

to recreate the atmosphere of being strapped down in a bucking studio

on the North Sea! DJs used to operating their own turntables found the

job was being performed by technical assistants. Radio One, still dogged

by 'needle-time' restrictions, was also required to share airtime with

the more formal Radio Two. The substitute for record-spinning was live

music. Embarrassing 'live house band' versions of Hendrix hits tended

to somewhat mar the station sound and its intended 'with-it' image.

The Beeb had a lot to learn.

The first independent commercial radio stations did not launch till 1973

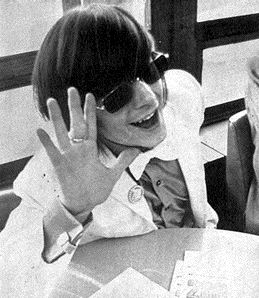

(Left:

Sony Golden Award-Winner 2002, the late John Peel. Famous for his 1967

Radio London programme 'The Perfumed Garden', arguably the most innovative

radio programme since Kenny and Cash in 1965)

Many of the country's top DJs, such as Ed Stewart,

Keith Skues and Tony Blackburn owed their careers to Radio London. Britain's

most innovative broadcaster ever and certainly one of the most successful

of all the Big L jocks, was the late Kenny Everett. Another innovative

Big L jock – the 2002 Sony Golden Award-winner, John Peel, was

still broadcasting on Radio One up until his untimely death in October

2004.

There is much more to the offshore radio story, which continued well

beyond the Sixties, but that's another saga for another day.

Mary Payne

Personal memories, summing-up the sadness of August 14th 1967 by David Skeates and Geoff Killick, are here.

Our report on the USS Density Reunion in Dallas, Sept 2001 is here in Branson, Missouri, Sept 2003, is here, in San Antonio, Texas, Sept 2008, is here.

DJ Bud Ballou's account of being aboard the Radio Caroline South ship as she was towed away, in March 1968, is here.

DJ Martin Kayne's account about the Radio Caroline North ship being towed away in March 1968 is here. The page includes a link to a newspaper report of the time regarding the two ships' overnight 'disappearance'.

A short section about Radio Luxembourg is on our website here.